|

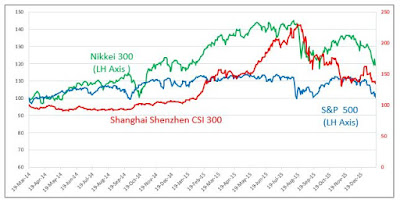

| Global Equity Market Composite Indexes |

Soon after the New

Year holidays was over markets volatility reappeared, stock prices started to tumble and the

fragility intensified. The signals are becoming much clearer that not only the

United States economy is slowing down, but also we are much closer to a new

financial crisis. These were, of course, expected. After the Fed’s first

interest rate rise, I wrote on December 15, 2015, that;

”it is hard to believe that an extra 25 basis point move … will provide any signal about the path of normalization, particularly when the situation in Europe and China is so precarious”.

And I predicted that:

“The more likely scenario is a heightened level of uncertainty and a possible financial crisis when this season’s holidays are over.”

In a backdrop

of a global growth that has increasingly conditioned on the availability

of central banks’ interest-rate stimulus and quantitative easing, several rationalizations

have been assumed would generate growth and correct imbalances; including soon

to be lower long-term interest rates, further market making efforts, generating expansionary wealth

effects and liberating ‘animal spirits’, which are noted as the so-called new policy tools for central banks to manipulate the level and slope of the yield curve! Assuming that these

policies have been successful in preventing a global melt-down after the Big Recession, a hypothesis

that its validity cannot be tested, it is clear that they have not been effective in generating

sustainable vigorous growth rates to close the gaps both in the labour and

goods & services markets. Furthermore, their distortive effects on capital

markets, favouring interest sensitive investments particularly in the

construction industry is creating an inertia that would hamper investment in

knowledge-based manufacturing and communication industries, pushing up high

debt levels even higher.

Back in the

July last year, I predicted the

continuous weakness in China’s stock markets and wrote:

“Just a quick glance at the Shanghai Se Composite Index (SSE) makes it quite clear that share prices were and still are overvalued.”I warned about the Fed's Balance sheet and suggested that

“the steady rise of share prices in the US cannot be entirely divorced from what happened in China. Yes, as Milton Friedman used to say ‘inflation always and everywhere is a monetary phenomenon’ and a greater part of this asset price inflation is also a monetary phenomenon. A Pandora's box that when opens up will be creating an enormous amount of misery.”A week later that month China’s stock market dropped by 8%. The Shanghai index dropped 3.6 percent on January 14th this year, contributing to a decline of more than 20 percent from its December high. Stocks in the United States fell to their lowest levels since late August. The S&P 500 stock index was down 8 percent for 2016 and close to 12 percent below its benchmark high reached in 2015, and the Russell 2,000, a measure of small-cap stocks, showed a 23 percent decline from its peak.

Encountering

the market volatility, investors are clamouring again towards fixed investments

like government bonds. As a result, the yield on the 10-year Treasury note

declined to 2.05 percent from 2.09 percent in the mid-January. Earlier they had dropped below 2 percent for the first time since October, indicating less appetite

for investing in capital formation, which is essential for the longer term

growth. It is true that the US is in the sixth year of a recovery that has seen her unemployment fall from 10 per cent in 2009 to 5 per cent in December 2015. But

as I wrote before it is the impacts of the US weak

capital formation that has artificially boosted the recent declines in the

unemployment rate. I wrote;

“The appearance of a gradual decline in the US economy's slack is attributable to a greater use of contingent labour and contingent capital, due to the prevailing global uncertainty.”The global uncertainty and ultra-loose monetary policies have hampered capital formation and encouraged businesses to follow strategies of incremental reductions in costs that are not accompanied by investment in new technology. Instead of investment businesses have resorted to capital-saving strategies, or have bought back their shares. I have suggested that due to high uncertainty businesses are reluctant to invest in irreversible capital, arguing that businesses

“would try to meet any increased demand by employing contingent workers. (...) In such conditions, businesses may lease equipment instead of purchasing, or may upgrade an existing production line with used equipment,”I went on to argue that this increased reliance on contingent labour and capital appears to be the key reason for a rapid decline in the U.S. unemployment rate, which in turn was used by the Fed to justify its interest rate increase in December.

In his speech of January 14th, James

Bullard President and CEO of FRB-St. Louis has argued that oil price movements

are an important component of headline inflation in the U.S. Of course this is

true, but a significant part of the decline in oil prices is due to the slowing of global growth not

only in China, but also in the United States and Japan. In fact, it is quite

probable that the U.S. annualised growth rate may have dropped, to less

than 2 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2015. In November 4th Fed Chair Janet Yellen told a House of

Representatives committee that if the economy were to deteriorate in a

significant way, "Potentially anything - including negative interest rates

- would be on the table.” The possibility of a negative interest rates has also

been raised by some other central banks including Bank of Canada.

The ECB has

been the first major central bank to set interest rates below zero in June

2014, and in its December move it slightly went lower to minus 0.3 percent. Sweden,

Denmark and Switzerland have also moved their policy rates below zero. In Japan,

despite the fact that Bank of Japan Governor Mr. Kuroda has stated that he saw no need to

implement negative deposit rates, one could argue that the BOJ's massive

asset-buying program, dubbed "quantitative and qualitative easing"

(QQE) is tantamount to a declaration of negative interest rate. It is not yet clear a negative interest rate policy would be

effective, and one could legitimately argue that this policy is the other side of the

coin in the recent currency wars.

Sooner or later

central banks must or will realize that they are ill-equipped to deal with the

current global economic malaise. The coordination failure of fiscal and trade

policies on the global level for the urgently needed structural reforms to deal with unsustainable debts,

insolvent banks, break-down of healthy

transmission mechanisms is exacerbating the

imbalances, worsening inequality, increasing poverty and may lead to disastrous

conflicts.

No comments:

Post a Comment